7th Release – Medical Expenditures and Hospitals

Part #1: 2022 Reform of Medical Fee Structure; what you see, what you don’t

Note: The opinion of the author expressed in the article does not represent any official opinion or position of Medical Data Vision regarding the 2022 Reform of the Medical Fees. The series of article is designed to provide insight and matter to discuss the healthcare environment among various stakeholders. Thanks for your understanding.

Introduction

3 months have passed since the revision of medical fees in 2022 became effective on April 1. Please refer to MDV column “2022 Medical Fee Revision Overall Review” published earlier where the detailed content of the revision was introduced. Both the revision and the “community medical plan” aim at the differentiation and cooperation between different bed functions, following the design of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare to address the baby boomer generation passing over 75 years old in 2025. Housing, medical care, long-term care, prevention, and living conditions form the key aspects of the “comprehensive community care system” that provides the core to the next revision scheduled for 2024. Hospitals are facing many issues now and in anticipation of those future changes. Our goal is to review the various aspects of the existing and future policies with a new column to be released on the last working day of each month over the next 7 months.

What do we see in the 2022 revision of medical fees?

On June 1, 2022, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare announced that the number of hospitals subject to “DPC / PDPS” (Disease Procedure Combination/Per-diem Patient System) was 1,764 (+9 vs. previous year), and the number of target beds was approximately 480,000. It was announced that the “diagnosis group classification” included 502 injuries and illness names (previous ± 0) and 4,726 in diagnosis group (including CCP matrix classification, +169 codes compared with the previous year). CCP stands for Co-morbidity Complications Procedures, where even for patients with the same illness, the same treatment, and the same surgery, the same DPC code is selected, but sub-categorized according to clinical findings, such as the time and age of onset, and the degree of consciousness to reflect on the treatment complexity. This subcategorization leads to a significant increase of new codes. For example, in the case of cerebral infarction, there are only 7 billing patterns. In addition, it was announced that the number of DPC preparatory hospitals would reach 259 (+12 in the previous year).

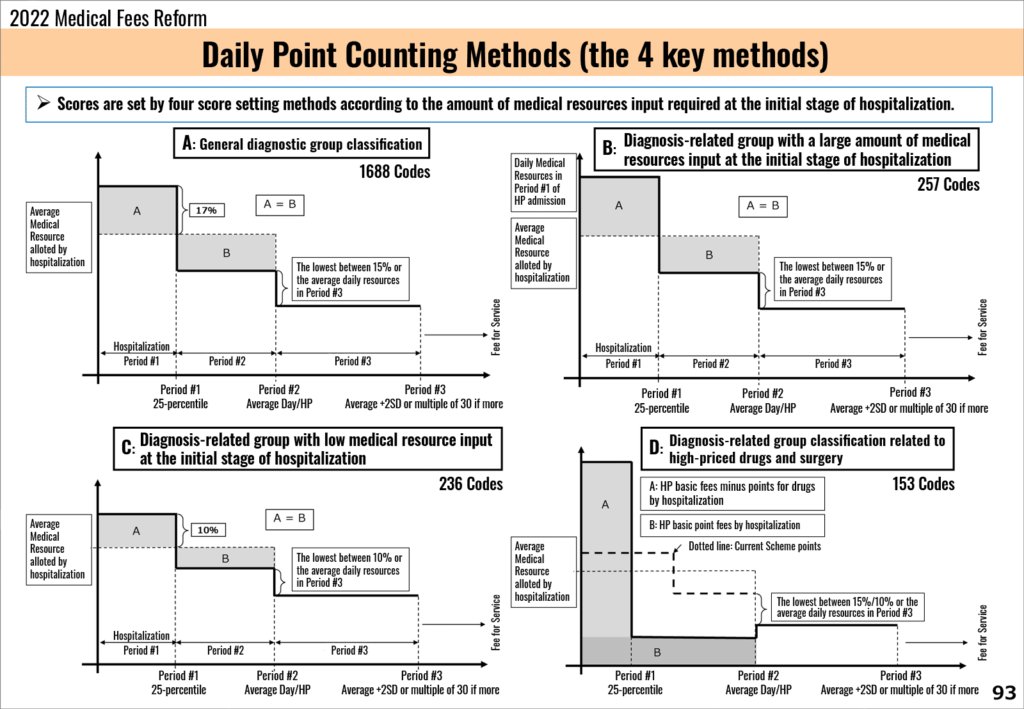

Since the “DPC / PDPS” system was introduced in 2003, there have been many additions and subtractions contributing to the system’s adjustment, so the limited number of changes observed in the 2022 Reform led a few to consider that the system may have entered its maturity phase. However, while the structure remains, there have been many changes in the DPC scoring method for billing, for example in the A Method (see graphic below), the daily allowance putting more weight on the initial stage of hospitalization (period #1). Even in case of emergency hospitalization, one should expect the increase of medical resources at initial stage to translate in more limited resources for comprehensive medical care. We can observe such changed in the D Method part that includes codes for chemotherapy and short-term stay surgery.

Among the codes under revisions, we listed 153 of them and the general observation is that the combination of changes in the A Method and D Method can be suspected to strengthen the efforts to shorten hospitalization stays.

Reference: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/12400000/000943459.pdf

Looking further at hospital charges other than DPC, to clarify the role of specific hospital charges, a review of the admission conditions clearly set out the trend for distinctive coding between acute phase and post-acute phase. The roles of acute vs. convalescent / chronic hospitals have been clearly differentiated, setting the trend for further specialization of medical institutions.

What is still invisible?

Whether it is “DPC / PDPC” or “specific hospitalization fee”, if you interpret the system well, even if you look at various types of fees, for example the drug, the procedure of treatment, or the examination items, they should all be counted as hospitalization fee. In other words, hospitalization somewhat includes the notion of “Comprehensive Care”.

Also, if you look at each DPC code, you can see the deduction of daily allowances due to the deduction of drug prices, but from the overall picture, if you can be discharged with the same average length of stay as observed in other medical institutions, outside the drug cost we observe that the hospital charges are properly covered with the new scoring structure.

On the other hand, regarding the facility standards for “general hospitalization fees for the acute phase”, the evaluation requirements for severity and medical and nursing needs have been reviewed, because some medical facilities calculate hospitalization fees that do not match the actual conditions of inpatients. By exposing the lack of resources and applying stricter discipline, the intent is to get closer to the ideal number of beds structure advocated by the “Community Comprehensive Medical Care Concept”, although the trend does not seem to progress as expected by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare.

To build the ideal “comprehensive community care system”, the recent consensus is to secure a post-acute / sub-acute bed infrastructure, however as a hospital, whether to maintain an acute hospital structure or to switch to a convalescent hospital status is a very critical choice to be made. The stake goes far beyond the issue to “maintain the management of the current hospital scale”, and the answer is hard to be found.

For More Information, Please Contact Us Here

About Japanese Healthcare System

What you need to know about the healthcare system in Japan before using the data.

SERVICE

In addition to various web tools that allow you to easily conduct surveys via a browser using our medical database, we offer data provision services categorized into four types to meet your needs and challenges: "Analysis reports" "Datasets," "All Therapeutic Areas Data Provision Service," and "Specific Therapeutic Areas Data Provision Service.

© Medical Data Vision Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved.